Annual Market Returns 1927-2008, cap-weighted NYSE/Amex/Nasdaq:

Eugene Fama and Kenneth French posted this graph along with historical analysis of equity market returns, the equity risk premium, and equity market volatility. It is a very informative post, and basically shows that for financial markets 2008 was especially volatile, and it was an extreme event, but was not completely over the edge. Such a large negative return has a roughly 1.18% chance of occurring (if you assume a normal distribution, which isn't perfectly accurate). Statistically, this means that such an event should occur roughly once every 85 years. The last time it happened was in the early 1930s, or seventy-some years ago.

The graph actually surprises me: I'd expected much less movement in general. The mean year-by-year market return has been 11.39% since 1927, with a standard deviation of 20.75%. That's a lot of movement. Fortunately, as we can tell just by eye-balling the graph, the trends are largely positive.

This sort of historical context is important to remember when discussing policy. Markets have had catastrophic collapses before, and they will again. But recovery is basically assured, and overreactions look silly in due course. The next time someone talks about a "crisis of capitalism" keep this graph in mind. That does not mean that it is impossible to improve the system to lower the probability of a recurrence of these sort of events. But tweaks on the margin are one thing; over-hauling the system in response to a rare event is quite another.

(updated for clarity)

IPE @ UNC

Bookshelf

Tags

Blog Archive

-

▼

2009

(521)

-

▼

May

(36)

- How Much of an Outlier Was 2008?

- Just How Irrelevant Am I?

- Oil is creeping back up.

- Self-Outsourcing?

- Differing Views on China

- On the (Ir)relevance of IR Scholarship to Policy M...

- Bad News for Microfinance Proponents

- Political Incentives and the Israel/Palestine Situ...

- Handicapping the Upcoming E.U. Parliament Elections

- Social Science Smackdown Week!

- Props

- We Can't Stop Carbon Emissions (redux)

- Mo' Money, Less Problems

- Quote of the weekend.

- More on US/EU Unemployment

- Links for the Weekend

- Interesting Links.

- Seppeku

- US Unemployment Rate Higher than Europe's?

- Helping the Poor by Giving Them Money

- Happiness Is Keeping Poor People Away

- Blame Game

- Nye and Drezner on Policy Relevance, Academia and ...

- From "Obscure Journal" Article to Mainstream Policy

- Is Obama the New Nixon?

- Cognitive Dissonance and the Financial Crisis

- The Risks of the Intertemporal Carry Trade

- In Which French Winemakers Act, Well, French

- Who Gets E.U. Farm Subsidies?

- More 'Crisis of Capitalism' Hyperbole

- Pass the Cheese

- This Is How We Do It

- Hedge Funds Fight Back

- We Can't Stop Carbon Emissions

- Everybody Get Down

- Videos for the Weekend: Recent TED Talks

-

▼

May

(36)

Sunday, May 31, 2009

How Much of an Outlier Was 2008?

Labels: Business cycle; recession; financial crisis, stock marketsJust How Irrelevant Am I?

I very much appreciated Dr. Oatley's take on the irrelevance of much IR academic work to policymakers, and how that isn't necessarily a bad thing. I am in full agreement up to a point: the change in the discipline from deductive to inductive research, or from "grand" to "mid-level" theory-building, explains much of the gap between academics and policymakers*. Much modern research is concerned with fitting past data onto models, or developing post-hoc explanations for political phenomena. These may be of limited use for policymakers. The following paragraph, however, struck me as a bit odd:

Contemporary IR’s lack of policy influence is therefore the inevitable consequence of the field’s effort to become more scientific given what we seek to explain. Although economics has powerfully influenced our quest for rigor, the belief that policy influence is the natural consequence of this endeavor suggests that we have lost sight of how IR differs from economics. Economics as a social science (along with sociology and perhaps psychology) tells politicians how to use policy to change social outcomes. IR as a social science explains why governments adopt some policies rather than others. The better we are at explaining the choices that governments make, the fewer novel insights we can offer to policy makers.

Modern economics seeks to explain what people (including politicians) can choose; i.e., the range of feasible options given the constraints that everyone faces. Political science seeks to explain what people (esp., but not only, politicians) actually do choose. Now, it is true that we often model political actors as rational actors, but in the more sophisticated research these actors are boundedly rational (i.e. subject to biases like everyone else) and/or face incomplete information.

If IR research can improve the quality or amount of information that policymakers have at their disposal, then IR scholarship can have relevance for policymakers. For example, if we can provide insight into the political incentives facing national leaders, then perhaps we can affect the way that policymakers approach diplomacy. If we can provide tools for interpreting past behaviors in more rigorous ways then we may be able to help policymakers interpret signals and intentions. Academic scholarship can frame the issue in ways that are not always immediately obvious.

It's possible that much IR research is of little or no practical use to policymakers, but some of it may have utility. And if the recent economic crisis has taught us anything, it is that future events can make past theories seem much more relevant than they seem today.

*Although it should be said that this wasn't really Nye's original point; he was complaining about a lack of academics in the policy world, and the incentive structures that contribute to that gap.

Saturday, May 30, 2009

Oil is creeping back up.

Labels: Economics, Oil, recovery, speculationGas prices have increased by 20% over the last month (and jumped 90 cents since January), and the price of a barrel of oil has more than doubled since February closing at $66.31 at the end of trading on the NYMEX on Friday afternoon. With the daily news cycle fixated on the appointment of Sonia Sotomayor to the U.S. Supreme Court, the erratic (but, not really) actions of the DPRK and their recent nuclear test, Susan Boyle coming in second on Britain's Got Talent, and of course Prince Harry visiting New York City on his first official U.S. visit, the talk of increasing oil prices has been relegated to the back pages barely getting attention from policymakers and the media.

Self-Outsourcing?

The Onion (one of America's greatest news sources) released this amazingly funny video on self-outsourcing. Enjoy!

More American Workers Outsourcing Own Jobs Overseas

Friday, May 29, 2009

Differing Views on China

Labels: Dollar; China; Currency Manipulation; Exchange RatesObama and Geithner want structural adjustment of the Chinese economy and some upwards movement on the value of the RMB relative to the dollar.

Scott Sumner wants to see the RMB devalue against the dollar. Not a typical viewpoint (at least among non-economists), but he has some very good reasons.

In the first scenario, China stops funding the U.S. debt by buying Treasury bills. In the second, they continue that practice. For a very good article discussing the choice Beijing must make, see this piece by David Leonhardt.

On the (Ir)relevance of IR Scholarship to Policy Makers

In April, Joseph Nye initiated a discussion about the policy relevance of contemporary international relations research. Dan Drezner pushed the discussion further, inviting academics to weigh in. (Will posted the blogging heads version last week). The central questions are two: why does contemporary IR scholarship have so little impact on policy? What, if anything, should or could be done about this lack of influence? Answers focus on the incentives that scholars face within the academy, with some focus on the supposed methodization of IR scholarship.

Yet to be articulated is the recognition that given what IR strives to do as a social science, any advice we might offer to policy makers must be either redundant or wrong. This is probably overstated, but let me defend it before I qualify it.

As a social science, IR strives to explain the choices that politicians make. The models we develop therefore either accurately explain governments' policy choices or they are wrong. IR models that accurately explain the decisions that governments make offer no insights to the politicians whose behavior they model. In fact, the more our models become grounded in empirical observation, that is, the more they summarize how politicians typically behave, the less useful they become to the politicians whose behavior they summarize. On the other hand, when politicians make choices that our models do not explain, our models must be wrong; after all, our models purport to explain politicians’ choices. Consequently, the only policy-relevant advice that IR can offer must be either redundant or wrong.

This problem is compounded by the incentive problem. Contemporary IR models assume that politicians respond rationally to incentives. What this means concretely will obviously depend upon context. Yet, the notion that a politician would adopt a fundamentally different policy than the one currently in place after learning about a piece of IR scholarship assumes that policy choice is predominantly a matter of intellectual persuasion. Thus, what we assume to be true in our models (politicians respond to incentives) is inconsistent with what must be true in order for our models to influence governments’ policy choices (politicians respond to intellectual persuasion). This implies that contemporary IR models can influence policy only if they fundamentally mischaracterize the nature of political decision making.

Contemporary IR’s lack of policy influence is therefore the inevitable consequence of the field’s effort to become more scientific given what we seek to explain. Although economics has powerfully influenced our quest for rigor, the belief that policy influence is the natural consequence of this endeavor suggests that we have lost sight of how IR differs from economics. Economics as a social science (along with sociology and perhaps psychology) tells politicians how to use policy to change social outcomes. IR as a social science explains why governments adopt some policies rather than others. The better we are at explaining the choices that governments make, the fewer novel insights we can offer to policy makers.

The subtext of the broader discussion seems to suggest that we should lament this. I don't see why. We give up the opportunity to offer poorly-conceived policy advice in favor of gaining systematic knowledge. We could benefit by being more self-consciousness about the consequences of the choices we make. In particular, because our commitment to social science necessarily renders us less useful as policy advisers, we must invent new justifications for the project in which we are engaged. That, however, must be the topic of another post.

Bad News for Microfinance Proponents

The results of the first randomized trial of the effects of microfinance are in [pdf], and the conclusion is mixed:

On balance our results show significant and not insubstantial impact on both how many new businesses get started and the profitability of new businesses. We also do see some impact on the purchase of durables, and especially business durables. However there is no impact on average consumption, though as we will argue later, there may well be a delayed positive effect on consumption. Nor is there any discernible effect on any of the human development outcomes, though, once again, it is possible that things will be different in the long run.

Basically, microfinance is good for those who are already have businesses but need some cash to make investments that boost productivity. It may make it possible for some others to start their own businesses, but the evidence for this is indirect. Its effect on "human development" indicators like health, education, or women's empowerment is basically nil, although the study only looks at short-term effects. In short, the effusive language often used by microfinance proponents may have to be toned down a good bit. Pointer from the World Bank's PSD blog, which notes:

As the authors note, the impact of microfinance in education, health, etc. may not appear for quite some time. In normal times, we would just wait another year or so and take another survey. However, the financial crisis means these are not normal times. If, in a year or two, a new set of results appears to indicate no impact on human development, the randomistas could claim this as a failure of microfinance. In turn, the microfinance proponents will claim that the financial crisis invalidates the findings, arguing that the ROI for small-scale entrepreneurs was abnormally low due to the crisis. Unfortunately, we'll simply have no way to know for sure who's right.

Back in February, erstwhile co-blogger Sarah had a post on the effects on microfinance of the global economic downturn. It is here.

Thursday, May 28, 2009

Political Incentives and the Israel/Palestine Situation

Labels: Incentives, Political SurvivalMatthew Yglesias asks a question about the American government's willingness to pressure Israel into ceasing settlements in Palestinian territory:

Unfortunately for us, we’re not in one of those periods of time when Israel has a government that’s probably actually not that sympathetic to the settlers but faces domestic political difficulties in cracking down on them. If that were the case, then strong words from the United States might be enough to force change in Israeli policy. But the current government is a coalition between the right and the far-right, and gives every indication of being extremely committed to settlement expansion. This, naturally, raises the question of what American policymakers are prepared to actually do about the fact that the world’s largest recipient of American aid seems to have so little interest in our perspective on crucial regional issues.

"Our perspective" is in fact a reference to Yglesias' perspective, which happens to be roughly in line with Obama's perspective. But it is not necessarily the perspective of the public at large, who tend to side with the Israeli government come hell or high-water. Politicians want to stay in office, and the best way to do that is to get the public on your side. In this case, that means taking a hard-line approach against the Palestinians:

[T]he thrust of US policy in the region derives almost entirely from domestic politics, and especially the activities of the ‘Israel Lobby’. Other special-interest groups have managed to skew foreign policy, but no lobby has managed to divert it as far from what the national interest would suggest, while simultaneously convincing Americans that US interests and those of the other country – in this case, Israel – are essentially identical.

Now, I don't entirely agree with the 'Israel Lobby' argument advanced by Mearsheimer and Walt, but the broader point is impossible to deny: the broad public sides with Israel over the Palestinians for a variety of reasons. This is evident in both political parties and in every national election. Indeed, last week 76 U.S. Senators sent a letter to Obama urging him to "support Israel" without conditions but to demand a host of concessions from Palestine before affirming its right to a state. (Interestingly, the Jerusalem Post article linked above omits the senators' affirmation of the Palestinians' right to a state if they achieve certain pre-conditions; this AFP story keeps the relevant passage in. The letter itself is here [pdf].) This is actually a very different line than the one Obama is taking -- a much harder line towards Palestine -- which shows that even a very popular president will have difficulty galvanizing Congressional support for any policy that is even remotely critical of Israel.

The lesson is that legislators respond to incentives just like anyone else, and the incentives are all aligned in such a way as to practically guarantee universal support for Israel in the Congress, because that is what the electorate wishes to see. So the Congressional movement that Yglesias wishes to see is very unlikely to actually happen.

Handicapping the Upcoming E.U. Parliament Elections

Via A Fistful of Euros, here is a handy primer from FiveThirtyEight. Forecasting is much more difficult in this case than in the last U.S. election:

As a result, quantitative evaluation and projection of the outcome of the elections is quite a challenge. Rather than only developing a projection model, such as FiveThirtyEight was able to do with the 2008 election cycle in the US, inter-party and intra-party dynamics in 27 countries must be analyzed. With around 250 parties running for seats in the EP, and 8 coalition parties vying for power in the Parliament, complications are many.

But maybe more interesting is the detachment many Europeans feel towards the process:

Another dynamic that shapes the EP elections is the dramatic lack of interest from most Europeans in the election. One British friend of mine, when I asked if he would be voting in the elections, insisted the UK did not have any MEPs, as they had not changed to the Euro from the British Pound. Recent Eurobarometer polling indicates that only 29% of EU citizens could identify the correct year for the next wave of EP elections, ranging from just 14% in the UK to 56% in Luxembourg. Even though more than 70% of respondents felt that “the EU is indispensible in meeting global challenges” and “what brings citizens together is more important than what separates,” just 34% of citizens planned to vote in this round of EP elections.

Similar melancholy over the elections were expressed by two E.U. citizens in my living room yesterday while watching the Champion's League final. But for those who are interested, FiveThirtyEight promises much more coverage over the next month as the election comes and goes. (Voting occurs at different times in different countries, but most E.U. citizens (some 80%) will vote from June 4-7.) FiveThirtyEight was indispensable during the American election season, so if they are able to do half as well for the European elections they will prove to be a valuable resource.

Social Science Smackdown Week!

There have been an awful lot of high-profile battles going on in the blogosphere lately. And I'm not talking about the typical blogger-vs.-blogger spats. I'm talking about big-shot social science Ph.D.s going at it hammer-and-tongs over issues directly related to public policy. A breakdown:

-- Richard Posner vs. Alan Greenspan on whether Greenspan deserves some blame for the economic crisis, with commentary by Megan McArdle (she calls this round for Posner).

-- Scott Sumner vs. Brad DeLong and Paul Krugman on the utility of models of asset-price bubbles. Of course, Sumner has been fighting with Krugman practically non-stop since joining the blogosphere.

-- A real-live bet (for money!) between Bryan Caplan and John Quiggin over U.S. vs. E.U. unemployment rates over the next decade. I previously covered this here.

-- William Easterly vs. Jeffrey Sachs, and Dani Rodrik, and Paul Collier, all on different aspects of development policy. Plus a bonus: Dambisa Moyo goes after Sachs, too! It's usually not nice to gang up, but then again, Sachs started it.

-- Robin Hanson vs. Andrew Gelman on the signaling motivations of the approaches conservatives and libertarians take to public policy, with a cameo by Tyler Cowen whose contribution was one pithy line: "don't forget the villains also".

Whew! I must say, I've tried to pick a few fights in recent days but nobody ever notices me (except dear Emmanuel, who is always willing to argue in favor of the proposition that I am either silly or stupid). But for fun, here's my scorecard on the above arguments:

1. Posner vs. Greenspan is a draw; Greenspan certainly bears some responsibility for the consequences of his actions, however it is hard to imagine anybody else in the same position doing much better (as evidenced by the fact that Greenspan had few critics until last Fall). I also think that Posner over-states his case.

2. Sumner vs. Krugman/DeLong goes to Sumner; even if Krugman and DeLong succeed in fitting past data onto a model, its utility going forward is probably close to nil.

3. I'd take Caplan's side over Quiggin's in their bet, but I think it'll be very close. Caplan's first proposal was pretty obviously skewed in his favor, which is why Quiggin forced a compromise. The new terms strike me as fair and much more interesting.

4. Easterly vs. Sachs goes to Easterly; Easterly vs. Rodrik is probably a draw; Easterly vs. Collier goes to Collier.

5. Hanson vs. Gelman goes to Gelman.

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

Props

Labels: security threats, UNCInspired by North Korea's most recent nuclear test, Dan Drezner offers a list of his favorite IR articles and books on the role that the reputations of states play in international relations. This isn't usually IPE fare (although several of the his favorites are IPE texts), but one thing about his list immediately stood out: an article by Mark Crescenzi, Associate Professor of Political Science here at UNC, made the list along such luminaries as Thomas Schelling, Daryl Press, Philip Zelikow, and some dude named Machiavelli. The list is here, and Dr. Crescenzi's article may be found at JSTOR here (I do not know of an ungated version). I can second Drezner's recommendation: it's a very good article.

We Can't Stop Carbon Emissions (redux)

Ryan Avent takes Wilkinson to task for having the audacity to claim that there may be some collective action problems involved in getting the major world powers to credibly commit to reduce their carbon emissions, and in the process unwittingly stumbles onto the principle problem in international relations: in the absence of an over-arching international authority, cooperation among states is very difficult to achieve. Problem is, he has no idea that he's stumbled onto any problem at all. In fact, he denies that there even is a problem:

This seems almost deliberately dense. In particular, it makes no distinction between the world of billions of daily, anonymous transactions and the world in which a handful of great powers attempt to hammer out a diplomatic agreement. Unsurprisingly, it's very difficult to get millions of urban denizens to voluntarily come together to build and fund a road network or transit system in the absence of a coercive mechanism. The benefits are too broadly shared, and the incentive to free ride too great. But the smaller the number of players, the more concentrated the benefits, and the easier it is to find a mutually beneficial agreement. ...

In fact, there are fewer than ten relevant players, and only two really relevant players not already committed to reductions -- the US and China. Given that climate negotiations are part of a repeated game between the two great powers (that is, they're more or less constantly talking about one economic or political issue or another), it seems very likely indeed that an American pre-commitment to emission reductions would facilitate a similar Chinese commitment.

Ignore the rich condescension for a moment, and the irony as well. Avent is poking around at a game-theoretical argument: an over-arching international government isn't necessarily needed, because we only have to get a "handful of great powers" to agree to things, and coordination is easier with a smaller number of players. Well, that should be simple then. But there are all sorts of problems with this.

First, while it might be true that it is easier to coordinate among fewer players, it isn't necessarily true. In many game-theoretic models the number of players is irrelevant: coordination is just as difficult with 2 players as it is with 2,000. In other models, there may be lots of players, but only some have any ability to influence the final decision. In the picture Avent is trying to paint, this is actually the case: despite there being 200-odd states, really all that's necessary is securing the commitments of a relatively small number of those.

But even if Avent were completely correct about this, he's missing something else entirely: the salience of the issue. It's easier to tax millions of people a small amount and build roads with the proceeds than it is for neighbors in a property dispute to resolve the matter without litigation. If Avent's story were complete, this would not be the case. But the history of international relations is filled with instances of disputes between two states that lead to very costly wars or trade disputes. This occurs when the salience of the issue is high, or when the costs of some action are sufficiently high to dissuade a state from taking that action.

Finally, even if states could negotiate an agreement, there is no mechanism to prevent them from defecting. States say one thing and do another all the time, especially in violation of multi-lateral agreements like this. This is what Wilkinson was really driving at, and Avent doesn't even seem to consider the possibility. But this is a very, very big problem. In a nutshell, this is what the study of international relations is all about: finding the conditions under which actual cooperation occurs, and not just cheap talk. Turns out, it's harder then one might think, especially if the major powers are in major disagreement as in this case.

Even Avent's own examples speak to this: he says that of the "necessary" handful of countries needed to reach a meaningful agreement, only the U.S. and China have not committed to reducing emissions. Well, perhaps, but an agreement is not the same as an actual change in behavior. Among E.U. states, only the U.K. and Sweden are on track to meet their Kyoto obligations by 2010, and the U.S. has actually had fewer increases in emissions than many countries that ratified the treaty (including Canada and Australia, as well as a half-dozen or so E.U. states). The incentive will always be to defect, because compliance is costly and enforcement is essentially impossible. One simply cannot assume, as Avent does, that these collective action problems magically disappear if a formal agreement is made. In fact, Avent does worse than that by arguing that if the U.S. could only lead the way, China would surely follow. Really? He's never heard of the free-rider problem? When have the Chinese followed the U.S. on anything? China has given absolutely no indication that they will be willing to curb emissions if that means reducing economic growth by any calculable amount. Nor can the Chinese regime halt growth and still remain in power. And without China, the world's largest polluter (and the gap is growing amazingly fast), no overall progress can be made. And this says nothing of India or Brazil or Eastern Europe or Southeast Asia or Africa (if that continent ever starts achieving real growth). Getting real global cooperation on this issue would be the single greatest achievement in the history of international institutions. Which makes it very unlikely that it will happen.

In any case, Avent is arguing in this way to support the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade legislation currently in the U.S. Congress. Strangely, Avent doesn't even like this bill, calling it "highly imperfect" and "totally inadequate". He also acknowledges that more progressive legislation is politically impossible despite an amazingly popular president who campaigned on this very issue and exceptionally large majorities in both houses of Congress. (Indeed, even this watered-down bill is unlikely to become law.) So Avent finds himself using deeply flawed logic to argue in favor of a wasteful, ineffectual bill that will make some people worse off by imposing a series of costs on them, but will not make anyone better off. He hopes that this bill will create better options in the future, but why? The electorate seems more likely to oppose future actions if present actions are wasteful and ineffective.

This is all odd, because Avent is usually much better than this, and he certainly knows enough economics to know better. So what's going on?

For even more difficulties, please see Tyler Cowen and Jim Manzi, and this previous post by me.

Monday, May 25, 2009

Mo' Money, Less Problems

Labels: development

KPC just posted the above picture, taken from research by Justin Wolfers. The picture shows the correlation between the U.N.'s Human Development Index (HDI) and per capita income. The correlation is .95, meaning that the two things are almost perfectly correlated. In the social sciences, relationships this strong are exceedingly rare.

HDI is an attempt to compare development outcomes across countries in a more nuanced way than simply looking at GDP numbers. So it includes things like educational enrollment, life expectancy (at birth), and adult literacy as well as per capita GDP. The thing is, those things are all highly correlated with per capita GDP. So even though the intention is to give a more nuanced view of quality of life than simply comparing income levels across countries, what we end up seeing is that income levels are the primary determinant of quality of life.

This shouldn't be too surprising. After all, if you have more money you can buy better health care (and thus live longer) and afford to send your children to school (thus boosting literacy and educational enrollment). However, simply comparing incomes across countries is often thought of as being a crass way of measuring quality of life. After all, money can't buy love or happiness, right? And if we spend our lives selfishly chasing money than we are surely missing other things.

That may be true, but it doesn't show up in cross-national studies. Wolfers has also done other work on the relationship between income and happiness (discussed here briefly; the actual research is here). This work (with Betsy Stevenson) re-examines the "Easterlin Paradox" that has caused much debate in the social sciences for decades. The Easterlin Paradox states that citizens of countries with more economic growth are not happier than citizens of countries with less economic growth, as was commonly assumed by economists. The inference was often made that there is no relationship between income and happiness. But the Stevenson/Wolfers research indicates that this isn't true, and the Easterlin Paradox doesn't actually hold: higher levels of GDP are strongly related with higher levels of subjective happiness.

This new research all points in the same direction: higher economic development leads to better objective and subjective outcomes. People in richer countries live longer, more enriching, happier, more fulfilled lives. So if we want to improve peoples' quality of life, then we need to improve their economic opportunities. And if we don't do that, we will have a difficult time improving outcomes.

Sunday, May 24, 2009

Quote of the weekend.

Labels: deductive economics, Economics, empiricism, inductive economics, riskI posted a link a couple of days ago to Barry Eichengreen's recent article "The Last Temptation of Risk" in The National Interest. But I thought I'd isolate a key bloc of paragraphs for our readers, in case you hadn't had the time to read the piece or clicked on the link and decided it was far too long, especially on a nice early summer weekend to read:

WITH THE pressure of social conformity being so powerful, are we economists doomed to repeat past mistakes? Will we forever follow the latest intellectual fad and fashion, swinging wildly—much like investors whose behavior we seek to model—from irrational exuberance to excessive despair about the operation of markets? Isn’t our outlook simply too erratic and advice therefore too unreliable to be trusted as a guide for policy?

Maybe so. But amid the pervading sense of gloom and doom, there is at least one reason for hope. The last ten years have seen a quiet revolution in the practice of economics. For years theorists held the intellectual high ground. With their mastery of sophisticated mathematics, they were the high-prestige members of the profession. The methods of empirical economists seeking to analyze real data were rudimentary by comparison. As recently as the 1970s, doing a statistical analysis meant entering data on punch cards, submitting them at the university computing center, going out for dinner and returning some hours later to see if the program had successfully run. (I speak from experience.) The typical empirical analysis in economics utilized a few dozen, or at most a few hundred, observations transcribed by hand. It is not surprising that the theoretically inclined looked down, fondly if a bit condescendingly, on their more empirically oriented colleagues or that the theorists ruled the intellectual roost.

But the IT revolution has altered the lay of the intellectual land. Now every graduate student has a laptop computer with more memory than that decades-old university computing center. And she knows what to do with it. Just like the typical twelve-year-old knows more than her parents about how to download data from the internet, for graduate students in economics, unlike their instructors, importing data from cyberspace is second nature. They can grab data on grocery-store spending generated by the club cards issued by supermarket chains and combine it with information on temperature by zip code to see how the weather affects sales of beer. Their next step, of course, is to download securities prices from Bloomberg and see how blue skies and rain affect the behavior of financial markets. Finding that stock markets are more likely to rise on sunny days is not exactly reassuring for believers in the efficient-markets hypothesis.

The data sets used in empirical economics today are enormous, with observations running into the millions. Some of this work is admittedly self-indulgent, with researchers seeking to top one another in applying the largest data set to the smallest problem. But now it is on the empirical side where the capacity to do high-quality research is expanding most dramatically, be the topic beer sales or asset pricing. And, revealingly, it is now empirically oriented graduate students who are the hot property when top doctoral programs seek to hire new faculty.

Not surprisingly, the best students have responded. The top young economists are, increasingly, empirically oriented. They are concerned not with theoretical flights of fancy but with the facts on the ground. To the extent that their work is rooted concretely in observation of the real world, it is less likely to sway with the latest fad and fashion. Or so one hopes.

The late twentieth century was the heyday of deductive economics. Talented and facile theorists set the intellectual agenda. Their very facility enabled them to build models with virtually any implication, which meant that policy makers could pick and choose at their convenience. Theory turned out to be too malleable, in other words, to provide reliable guidance for policy.

In contrast, the twenty-first century will be the age of inductive economics, when empiricists hold sway and advice is grounded in concrete observation of markets and their inhabitants. Work in economics, including the abstract model building in which theorists engage, will be guided more powerfully by this real-world observation. It is about time.

Should this reassure us that we can avoid another crisis? Alas, there is no such certainty. The only way of being certain that one will not fall down the stairs is to not get out of bed. But at least economists, having observed the history of accidents, will no longer recommend removing the handrail.

More on US/EU Unemployment

Apropos of this post by Alex noting that the unemployment rate in the US is now the same as the average of European OECD countries, consider this passage from John Quiggin:

Advocates of the US system make much of the deterrent to hiring associated with employment protection laws, but they ignore the other side of the coin. When the economy is contract, employment protection laws do in fact protect employment (if they did not, they would have no adverse effect on hiring either).

On this basis there is nothing surprising in what we are seeing. EU unemployment rates should be higher in expansions and lower in contractions, which is exactly what is required for lower variance.

Which is better?

Short answer: that is a normative judgment. If my primary concern is improving the lot of the most people most of the time, I might think of it this way: if the "normal" state of a capitalist economy is for there to be more years of growth than recession, and I want to maximize the well-being of the most people for most of the time, then I'd go for the system with the higher variance, since a majority of the time people on the margins will be better off. Additionally, more flexible labor markets allow more labor mobility, which increases competition and boosts productivity. This, in turn, leads to additional economic growth as well as improvements that don't show up in GDP, like the improvements in home computers of similar price over time. Technological advances often generate positive social externalities that don't show up in raw GDP figures.

However, if my primary concern is to avoid sudden catastrophic outcomes for even a small minority of people, and I'm willing to trade off subtle gains for the majority to achieve that, then I might prefer the more stable, but less dynamic, European system.

Now, if unemployment increases in the Eurozone as both Alex and I expect it to do, then this might be a moot point. After all, you can't juxtapose dynamism with stability if one system or other has more of both. And it is worth noting that there is more inter-country variance in unemployment rates in Europe than across states in the US. But if there is a choice to be made, then the appropriate decision can only be made on normative grounds.

Bryan Caplan, who has his own normative views, offers up a bet:

The average European unemployment rate for 2009-2018 (i.e., the next decade) will be at least 1% higher than U.S. unemployment rate. The bet will be resolved when Eurostat releases its final numbers for 2018.

I'm happy to bet each of the three authors $100 at even odds. Will they accept?

So far, I don't believe there are any takers.

Saturday, May 23, 2009

Links for the Weekend

Labels: Miscellany-- Sumner wonders why DeLong and Krugman are trying to model asset-price bubbles, and compares them to alchemists. And not in a good way.

-- Martin Wolf agrees with me: the New Economic Order will look a lot like the Old Economic Order.

-- "Slapped by the Invisible Hand": The shadow banking system is a real banking system, and should be treated as such.

-- Easterly vs. Collier in which the former accuses the latter of statistical lies (i.e. "data mining"), plus Blattman's take and a shoutout to Karl Popper. So far, to my knowledge, Collier has not responded.

-- A new IPE book on the politics of global regulation.

-- Cowen and Singer on aid, development, poverty, and ethics:

Interesting Links.

A Special Report on International Banking from the Economist

Seppeku

The Japanese economy is, er, not doing well. Last quarter, GDP fell at an annualized rate of 15.6%. Exports in the first quarter were down at an annualized rate of 70.1%. That is not a typo, and the report is here [pdf]. Private investment was down at an annualized rate of 49.7%. As The Economist wrote: "If Japan does not hit bottom soon, it may revert to an agrarian feudal economy". Okay, maybe not. But still.

So what does the Japanese government do? Unemployment has increased by 25%, but the unemployment rate is still below 5%. The Japanese achieve this by subsidizing employment, which results in things like metalworkers planting herb gardens. They may as well be digging ditches and then filling them in again. This busywork keeps the official unemployment numbers low, but the labor is not being used productively, so the economy never really recovers. Rigidities in the labor market make things worse: life-time employment is a matter of national obsession, so opportunities for young workers are scarce.

This has been Japan's story for well over a decade now: subsidize employment through round after round of fiscal stimulus (while keeping interest rates low). And what have they gotten? Employment without growth, jobs without opportunities, low unemployment but also low productivity. Add to the mix the continuing existence of zombie banks and the result has been stagnation and deflation.

Any of this sound familiar?

There are many lessons to learn from the Japanese experience. One of them is that Keynesian stimulus may reduce measured unemployment without actually boosting output. That is, the economy may look like it is at full employment, but if the labor is being used unproductively then the wealth of the nation may not increase, and the well-being of the people may not be improved.

Friday, May 22, 2009

US Unemployment Rate Higher than Europe's?

Labels: European Union, global recession, Unemployment, United StatesIt is expected that when the April international unemployment numbers are released, the United States will have a higher jobless rate than Europe. The United States' rate is already on par with European averages, a factoid that would have surprised many just a few months ago.

For many years, unemployment in the United States was lower than in Western Europe, a fact often cited by people who argued that the flexibility inherent in the American system — it is easier to both hire and fire workers than in many European countries — produced more jobs.

In April, the rate in the United States rose to 8.9 percent. When the European figures are compiled, it seems likely that the American rate will be higher for the first time since Eurostat began compiling the numbers in 1993.

For men, the unemployment rate in the United States surpassed that of the 15 original European Union countries in December. By March, it was 9.5 percent in the United States, compared with just 7.5 percent for women. The figures for men and women in the 15 European countries, however, are close together, at 8.4 percent and 8.5 percent.

How did that happen during a worldwide recession? First, it appears that the safety nets in many Western European economies made it easier for people to keep their jobs as the economy declined. In Germany, programs allow companies to get government help in paying workers, for example, keeping them employed. If the recession becomes severe enough and long enough, of course, it could turn out those programs do not so much avoid the pain as defer it.

In the United States, there has been more movement of workers from depressed areas to places where the employment outlook is brighter. But the housing crisis appears to be hampering such movement because some workers own homes that are worth far less than the amount they owe on their mortgages.So I guess I'll add to the speculation. Another reason may be the extent and quality of European re-training programs and their ability to get workers back into the labor force after shorter adjustment periods. A vast chunk of the increase in American unemployment has come from financials, insurance, housing and retail (as well as unemployed graduate students argh!). Europe may simply have been less exposed to the problems in financials and housing.

Among the 15 European Union countries, the national unemployment rates range from 2.8 percent in the Netherlands to 17.4 percent in Spain. That is a wider spread than the ones among American states, where the rates range from 4.2 percent in North Dakota to 12.6 percent in Michigan.

Tuesday, May 19, 2009

Helping the Poor by Giving Them Money

Labels: development, Foreign AidNice little natural experiment, recounted by Aid Watch:

Two NGOs working in Zambia, Oxfam GB and Concern Worldwide, tried a different approach: they handed out envelopes stuffed with cash—from $25 to $50 per month per affected family, with no strings attached. An evaluation found that common fears about cash transfers—that the cash infusion will cause inflation in the market, that the money will be squandered, or that men will take control of the money—were unrealized.

What did people buy with the money? The list includes maize, beans, salt, cooking oil, meat, vegetables, clothes and blankets, paraffin, transport, soap and body lotion, and lots of other mundane household items. They also loaned it to friends, used it to pay back debts, purchased health care, education and transport, and rebuilt their homes. Only a very small fraction of the money (less than .5%) was spent on “unproductive” items, like liquor for the men.

This approach is different from traditional aid programs that distribute items like seeds, fertilizer, medical supplies, or other relief goods. Instead of doing this, simply giving cash can be quicker, more cost-effective, and actually allow the recipients to spend the money on things that have the most value to them. This seems like a pretty obvious strategy, yet it is fairly uncommon in foreign aid programs, or even domestic social programs (e.g. we give food stamps rather than cash). I think there are two primary reasons for this.

1. Paternalism, a.k.a. the "I'm afraid you'll buy booze with it" syndrome: When we help people, we want to see results. Unfortunately, what we consider to be good results are not necessarily what the aid recipients would consider to be good results. So we give seed instead of the money to buy it, or we give an apartment in a housing project instead of an equivalent amount of cash. This is fine and good if the aid giver's preferences are perfectly aligned with the recipient's preferences. Of course, that nearly never happens.

2. Politics: The majority of foreign "aid" programs are really direct subsidies to local producers, because we force the recipients to use the aid money to buy from certain firms. This "tied" aid often leads to inefficiencies and poorer outcomes, but that only matters if you care about the aid recipients over the domestic firms. Often, that isn't the case. This also happens domestically, as conditionality on food stamp programs are considered by some to be little more than welfare for American corn farmers.

What's the take away? If you want to help people who don't have much money, then give them money and let them spend it how they please. They'll do a better job getting the goods and supplies that they want and need than we could do, and there is basically no overhead costs of shipping, storing, and distributing goods. Therefore, more of the aid money can go directly to the needy rather than funding a supply chain.

And if they decide to spend it on booze... so what? If you're a Zambian subsistence farmer and your livelihood has just been wiped out in a flood, you might need a stiff drink more than a bag of seeds. Ditto if you're an American autoworker whose factory has just been closed.

P.S. Aid Watch has also hosted a nice little spat between Dani Rodrik and William Easterly over the utility of industrial policy in fostering economic development. It starts here, then here, and finishes here.

Monday, May 18, 2009

Happiness Is Keeping Poor People Away

Labels: immigration, income inequality; globalizationMatthew Yglesias posts a pretty picture showing a negative correlation between income inequality and income redistribution. This relationship is definitionally true, so at first I wasn't sure why he thought it was worth pointing out. But then he goes on to say that this means something else entirely:

I think the links between taxation, spending, and inequality are the most plausible explanation of the fact that the highest-taxed countries are the happiest. It can’t be that paying taxes makes Danes happy. But plausibly, living in a relatively egalitarian society makes people happy.

That certainly is plausible, especially to those (like Yglesias) who are attracted to arguments for progressive social policy from Rawls' "Veil of Ignorance". Unfortunately, as Wilkinson points out, the plausible causal inference isn't true:

Danes say they’re really happy and have the lowest inequality. But Americans are nearly as happy and have high inequality for an OECD country. Mexicans are a quite upbeat lot, but have really, really high income inequality. So there’s not much of a clear pattern in the data. The effect of inequality on happiness appears to be pretty strongly ideologically mediated. Unsurprisingly, high inequality tends to be disquieting to egalitarians. But it doesn’t so much bother meritocrats. Additionally, the causes of high inequality are various. Economic predation by political elites (lots of Latin America and Africa) is pretty likely to create a sense of victimization and injustice. But high levels of wealth creation in more or less fair institutions but with relatively little fiscal redistribution (the U.S.) doesn’t bother people as long as they think the system is more or less fair. So the national income inequality variable itself tends to have little or no independent effect. The effect it does have depends on other things people believe and care about and the specific causes of inequality in different places.

There are a lot of plausible explanations for why Danes are happy. One of them is that Denmark is a small, culturally homogenous country that preserves their homogeneity with strict immigration laws. These strict immigration laws prevent the migration of poorer people into Denmark, which keeps intra-national income inequality low (and possibly broadens the support for domestic redistribution, since the social spending won't go to immigrants) but increases the inter-national income inequality between Denmark and other, poorer, countries.

Yglesias does not describe which he prefers: within-country inequality or between-country inequality, and I'm sure he would recoil from having to make the choice. But there is often a trade-off. Without realizing it, he does seem to think that one of the two makes citizens happier, but I don't think he intends to espouse a "keep them out, keep them poor" attitude towards the developing world. Unfortunately, that appears to be the way it works: keeping immigrants out makes citizens of wealthy countries wealthier (on average), boosts support for income redistribution through social services, and makes people lucky enough to be born there happier than the unlucky ones born in poorer places.

This is why causal inference in the social sciences is so difficult: a plausible explanation isn't always borne out by the data. Sometimes this is made evident if we consider related questions. In this case, if we observe that poor countries are less happy than rich countries, which they are, should we conclude that it's probably because they don't have enough public transportation or a better pension system? Or maybe having access to better economic opportunities might improve the mood.

For the record, the other happiest countries are Finland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, Sweden, and Norway. Bastions of diversity, they are not.

Blame Game

It turns out that the collapse of the global economy was not caused by clueless economists or Gaussian copula functions or even big-headed quants. No, the blame for the financial Armageddon can be laid at the feet of a... political scientist. Well, sort of anyway.

So quick! Everybody get the torches and pitchforks! And after we've grown tired of blaming this guy for everything, I propose we blame Canada. It's always worked before.

(ht: Dani Rodrik)

Nye and Drezner on Policy Relevance, Academia and other topics.

This is a very interesting exchange between Joseph Nye of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard and Dan Drezner of the Fletcher School at Tufts. The two academics discuss the role that academia should have in policy debates, the policy relevance of IR scholars, and other interesting topics.

From "Obscure Journal" Article to Mainstream Policy

Cap and trade has become the "hot" environmental policy of choice as of late. Both those on the right and those on the left increasingly see it as the most efficient and practical way to tackle the issue of global warming using a market-based approach.

It is almost perfectly designed for the buying and selling of political support through the granting of valuable emissions permits to favor specific industries and even specific Congressional districts. That is precisely what is taking place now in the House Energy and Commerce Committee, which has used such concessions to patch together a Democratic majority to pass a far-reaching bill to regulate carbon emissions through a cap-and-trade plan.

The bill is poised to win committee approval this week, although with virtually no support from Republicans. If there was a single moment when cap and trade crossed the threshold from relatively untested economic concept to prevailing government policy, it came in May 1989 in the West Wing office of C. Boyden Gray, counsel to President George H. W. Bush.

Cap and trade evolved from an academic debate that began in the early 1960s when Ronald H. Coase, then a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, wrote an influential paper, "The Problem of Social Cost,” that examined when government should intervene in cases where a private entity causes public harm.

In 1971, W. David Montgomery, a Harvard graduate student in economics, fleshed out the idea of emissions trading in his doctoral thesis and has spent much of the last three decades trying to figure out how the marketplace can deal with environmental problems that are caused by relatively few actors but have consequences felt globally.

Sunday, May 17, 2009

Is Obama the New Nixon?

So asks Stephen Walt, and he also compares the current president to Carter and Clinton. This is Stephen Walt, so he's mostly talking about security initiatives, but there's a bit of IPE as well. Obviously, we have no reason to think that Obama shares the personal flaws of Clinton or Nixon; the post is purely about policy.

I tend towards Clinton for the obvious reasons: he's come into office following a Republican (Bush) administration, carries a "third way" flavor, has quickly ingratiated himself to other world leaders, has been exceptionally ambitious (but has probably bit off more than he can chew this early in his administration), and seems to have taken a pragmatic/technocratic approach to governance.

Obama is his own man, and parallels are in the eye of the beholder, so I wouldn't want to stretch anything too far. And yeah, this sort of game is kind of pointless, but it's also fun.

Cognitive Dissonance and the Financial Crisis

Good stuff from Niall Ferguson:

For reasons to do with human psychology and the failure of most educational institutions to teach financial history, we are always more amazed when such things happen than we should be. As a result, 9 times out of 10 we overreact. The usual response is to introduce a raft of new laws and regulations designed to prevent the crisis from repeating itself. In the months ahead, the world will reverberate to the sound of stable doors being shut long after the horses have bolted, and history suggests that many of the new measures will do more harm than good. ...

Human beings are as good at devising ex post facto explanations for big disasters as they are bad at anticipating those disasters. It is indeed impressive how rapidly the economists who failed to predict this crisis — or predicted the wrong crisis (a dollar crash) — have been able to produce such a satisfying story about its origins. Yes, it was all the fault of deregulation.

There are just three problems with this story. First, deregulation began quite a while ago (the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act was passed in 1980). If deregulation is to blame for the recession that began in December 2007, presumably it should also get some of the credit for the intervening growth. Second, the much greater financial regulation of the 1970s failed to prevent the United States from suffering not only double-digit inflation in that decade but also a recession (between 1973 and 1975) every bit as severe and protracted as the one we’re in now. Third, the continental Europeans — who supposedly have much better-regulated financial sectors than the United States — have even worse problems in their banking sector than we do. The German government likes to wag its finger disapprovingly at the “Anglo Saxon” financial model, but last year average bank leverage was four times higher in Germany than in the United States. Schadenfreude will be in order when the German banking crisis strikes.

This reflects one of my greatest fears. Most people know that the stock market indices are down over the past decade. Most people know that we are in a deep and serious recession. Most people (even academics and educated professionals) believe that this is due is "deregulation," although they do not have any knowledge about which specific deregulatory actions are responsible, nor do they have the faintest idea what regulatory changes would have prevented this crisis (or could prevent the next one). Some countries with relatively strict regulatory policies (e.g. India) have done fairly well in this crisis. Others have not. Some pessimistic economists (Roubini and Krugman) famously predicted a recession, but they had the trigger wrong (currency depreciation from mounting debt and trade deficit, rather than banking crisis) and incorrectly predicted recessions for years before this one came (perhaps they deserve credit for continuing to cry wolf until one actually materialized; perhaps not). Some have said that this financial crisis is the fault of the Bush administration and the Republicans, but the same people were not saying the same things during the last financial disruption in the late-1990s... when Clinton was in charge.

Ferguson goes on to say that much of the blame for the crisis can be chalked up to bad regulation (esp. Basel I and II) rather than deregulation. But as Ferguson notes earlier in the piece, "Financial crises will happen," and it's not easy to see in advance what the proximate causes of the next crisis will be. Basel I was a reaction to the exposure of Western banks to the Latin American debt crisis, while Basel II was a reaction to the Asian financial crisis. There is already a strong movement towards international regulatory policy harmonization in response to this crisis. But given recent history, there is little reason to be optimistic that regulators will be capable of preventing the next crisis. If the generals are always busy fighting the last war, how will they succeed in preventing the next one?

So what should be done? In my view, we should accept that financial crises will be a semi-regular feature in our economy, and try to institute regulatory institutions that will minimize the severity and duration of these crises. How to do that? By focusing our regulatory efforts on promoting transparency rather than trying to force banks into behaving well, by making our regulatory efforts counter-cyclical to give flexibility when needed, by limiting moral hazard (esp. the sort that leads to regulatory arbitrage), and by pursuing monetary and macroeconomic policies that lessen boom-and-bust cycles in the financial sector as well as the broader economy.

The last of these may be the most difficult, but also the most critical. The global savings glut and international macroeconomic imbalances had much more to do with the current financial crisis than any regulatory policy. In the future, we should understand that persistent macroeconomic imbalances will eventually correct, one way or the other. A gradual adjustment through the exchange rate mechanism is preferred to financial collapse and crisis. In the future, we should push for more flexible exchange rates, less public debt, and more openness in the financial system. This will not completely eliminate financial crises, but it may make them less severe.

Tuesday, May 12, 2009

The Risks of the Intertemporal Carry Trade

Labels: Debt

Back in February, I noted that Obama was engaged in a sort of intertemporal carry trade with the U.S. currency: he was gambling that the money he borrows in the present will be worth more than the money he has to pay back in the future. At the time, this made sense, since he could borrow at interest rates near zero (occasionally even at or below zero), and future inflation expectations were positive. Therefore, the present value of money actually was higher than the (expected) future value. Obama was arbitraging the system, and could have his cake and eat it too; he could spend today, pay back tomorrow, and earn a bit of profit on the side. He was able to do this because nobody wanted to lend to private corporations due to risk, and U.S. government bonds are perceived as being nearly "risk-less".

But there are signs that those days may be over. In March there was a failed bond auction in the U.K., indicating that bond traders were not interested in funding more deficits at rates the British government was willing to pay. Last week, something similar happened in the U.S.: the demand for T-bills was tepid, and investors demanded higher interest rates before buying. Why is this happening? For one, now that the dust has somewhat settled from the financial meltdown, investors are more willing to lend to (some) corporations. This creates competition for investment funds ex ante, which means that the government will have to pay a higher price to get the funds it needs to spend in deficit.

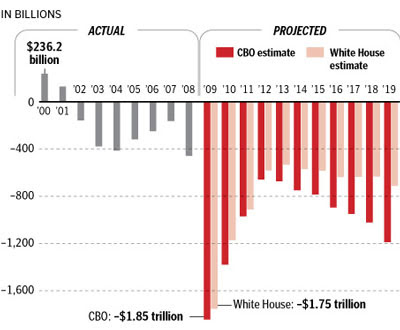

There is another aspect to this, however. Because of Obama's expansive deficits, which according to CBO estimates (see picture above) will still be well over $1tn in 2019, there is a rising fear that the U.S. will have to either default on its debt or inflate it away. In other words, there is a growing risk that the U.S. government debt will stop being considered "risk-free," and investors will demand a risk premium on T-bills. If that happens, then Obama will either have to scale back his spending programs (as Gordon Brown has done), raise taxes on a broader slice of the population than just the top 5%, or both.

Obama's carry trade bet looked like a win-win a few months ago. But that was contingent on demand for T-bills remaining high, keeping yields down, and allowing the government to arbitrage a profit (or very small loss). If that doesn't hold, then the whole thing will blow up in Obama's face, and the consequences for common Americans won't be pleasant either.

As many investors discovered last fall, the risks of carry trading are always the same: you don't want to be holding the potato when the music stops. The costs of unwinding are high.

Saturday, May 9, 2009

In Which French Winemakers Act, Well, French

Labels: EU; Agriculture; Common Agricultural Policy, globalizationMy previous post was about how large agri-business conglomerates capture much of the E.U.'s (and U.S.'s) farm subsidies. But common farmers and vintners get some too. And when you've been capturing rents for generations, being forced to give them up is a bitter pill.

Mr. Jeune, along with most French winemakers, opposes European Union plans to relax strict rules governing the making of rosé, or blush, wines just as they are starting to gain respect — and sales. Currently, red grapes are usually crushed and left to ferment briefly with the skins, the two being separated before the juice colors fully. The E.U. proposal would allow Europeans to simply blend red and white wine to create a pink blend — giving them the freedom to adopt the same, less complex, methods as New World producers.

“If you do this, why not allow people to make wine without any grapes at all?” Mr. Jeune asks, growing steadily more voluble over a glass of his own — “real” — rosé, from grapes grown in Provence. “You could do it in a laboratory, with alcohol, water, artificial flavors.”...

Though the French government seemed to go along with the blending proposal in January, it has since sought to block the measure after a backlash in the countryside. Because of its resistance, a final E.U. vote has just been deferred until June.

In France, a land reliant on agricultural subsidies, tiny producers with distinctive wines have a special place in national affections. Makers of the most exclusive French wines are prospering but, with competition from the New World growing, rosé is a rare midmarket success story — quite something for a product long considered inferior by wine snobs.

Yeah, yeah, I know: this all sounds very quaint. We in America often chuckle at these little squabbles. But these people are serious:

In March, La Baume winery in Languedoc suffered a bomb attack — the second in five years — and a shadowy group opposed to the “industrialization” of winemaking is blamed.

La Baume, a large winery once owned by an Australian company, Hardys, but since bought by a big French producer, Les Grands Chais de France, is seen as a symbolic target.

I suppose the message is clear: "If you don't use redistribution and government supports to protect our noble way of life from competition, then we'll blow you up, Weather Underground-style." Sounds like something Hollywood could work with, but I'd bet the noble French farmer wouldn't care much for that, either.

Speaking of films, Mondovino is a recent (last few years) documentary on the wine industries in Italy and France -- and the pressures they face from burgeoning winemakers in the Americas and elsewhere -- covers these issues very nicely. It focuses on the culture, but gets into some of the politics and economics as well. It is recommended viewing for those interested in agricultural policy, the differences between Americans and Europeans, IPE, and wine. Needless to say, I enjoyed it quite a bit.

Anyway, at least some are willing to put things into perspective:

But Anne Sutra de Germa, who runs a small winery, Domaine Monplézy, and also opposes change, is more optimistic.

“In some ways it’s good to have stupid laws,” she said, “because the consumer who wants good wine will, eventually, find us.”

Touché.

Who Gets E.U. Farm Subsidies?

French chicken farmers, Irish pudding makers, and Italian banks. Not at all the small-time farmer that proponents of farm subsidies often champion.

The U.S. is no better, by the way.

More 'Crisis of Capitalism' Hyperbole

In a recent op-ed, anthropologist David Moberg says that the current economic crisis is proof-positive that the institution of capitalism, and especially the cross-national finance flows that fuel it, need some serious re-thinking:

“Another ideological god has failed,” Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf wrote on March 9, referring to the neoliberalism—deregulation of markets, combined with state support for corporations—that President Ronald Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher first promoted aggressively in the ’80s. “The era of liberalisation contained seeds of its own downfall.”

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan admitted his fundamental operating assumptions that banks would wisely judge how much risk they could assume had been wrong. Former General Electric Chairman Jack Welch now says that the notion he promoted—that corporations should just focus on shareholder value—is “the dumbest idea in the world.”

The entire contemporary financial system was based on the assumption that financial markets were always efficient and rational. That idea fell off the cliff along with the world economy that it helped to wreck.

The build-up to the conclusion is disingenuous. Greenspan thought that banks would judge risk better than regulators. The banks surely performed badly, but there is little evidence that regulators would have done better. Indeed, the regulators that did exist failed just as badly as the private firms. Additionally, countries with stronger domestic regulators have not necessarily performed better in this crisis than countries with laxer regulatory structures. But this is mostly quibbling.

However the last paragraph cited above is flat wrong. The assumption is absolutely not that markets are always efficient and rational, which is why Alan Greenspan's most famous quote is about "irrational exuberance". On the other side, John Maynard Keynes (of whom Moberg approves) is famous for observing that "markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent". The assumption is that markets are efficient in the long run; indeed, much more efficient than the beliefs of one or a handful of people, including regulators. In the short run there will booms and busts, since information is not perfect and investors are "irrationally exuberant". These bubbles will then crash as investors become "irrationally pessimistic". People still move in packs, and investors are as prone to herd behavior as anyone else.

But in the long run these differences wash out. In the long run, information is perfect, or very near it. In the long run, markets aggregate information better than any other mechanism developed by man. This especially includes regulators. That assumption is what the financial system was based on, and that assumption has not been disproved. This economic downturn, like all economic downturns before it, has not damaged that idea.

Much of the rest of Moberg's essay is remarkable for its blandness: global imbalances certainly contributed to the economic crisis (however, he does not note that these imbalances were primarily caused by illiberal economic policies). He contends that regulatory change is needed, but casts aside proposals by Stiglitz and Rodrick in favor of... "a small tax on financial transactions". He says that we should "us[e] markets, not be used by them". Color me unimpressed. In the end, Moberg's subtitle -- "It is time to rethink capitalism" -- is proved vacuous: Moberg doesn't offer any clear proposals for change, nor any suggestions for what improvements could be made if we did reconsider capitalism.

But of course that's all Moberg can say. He knows that replacing capitalism as the dominant economic paradigm is both impossible and undesirable. Which is why I contend, yet again, that when the chips have fallen and the cards are down, the New Economic Order will look an awful lot like the Old Economic Order.

Friday, May 8, 2009

Pass the Cheese

Labels: Tariffs

Happy Day! The U.S. and E.U. have reached an agreement (pending approval by the necessary governments) whereby the U.S. lowers its prohibitive tariffs on Roquefort cheese, Italian mineral water, and other E.U. delicacies in exchange for laxer E.U. prohibitions on American beef. Believe it or not, but this brouhaha has lasted for 13 years, although it was amped up this Winter when Pres. Bush, in one of his last acts in office, hiked up these tariffs to bring the situation to a head (and then pass it off to Obama).

This Is How We Do It

At UNC, this is how we celebrate the end of a semester before we even take our finals. A bit presumptuous? Perhaps. But we prefer to think of it as confidence in the face of danger.

And at least it took place in the library, right?

(ht: KPC)

Wednesday, May 6, 2009

Hedge Funds Fight Back

Labels: BailoutHedge fund manager Cliff Asness has written an open letter to President Obama that has generated quite a lot of discussion in the blogosphere. Asness was apparently put off by Obama's claim that owners of Chrysler's debt should sell that debt to the government at whatever prices the government wishes to pay, and if they do not sell then they are "speculators" who "refuse to sacrifice like everyone else" and who are merely holding on "for the prospect of an unjustified taxpayer-funded bailout". Several of the juicier quotes:

Let’s be clear, it is the job and obligation of all investment managers, including hedge fund managers, to get their clients the most return they can. They are allowed to be charitable with their own money, and many are spectacularly so, but if they give away their clients’ money to share in the “sacrifice”, they are stealing. ...

The President's attempted diktat takes money from bondholders and gives it to a labor union that delivers money and votes for him. Why is he not calling on his party to "sacrifice" some campaign contributions, and votes, for the greater good? Shaking down lenders for the benefit of political donors is recycled corruption and abuse of power. ...

I am ready for my “personalized” tax rate now.

Asness has a right to be angry. Hedge funds have not taken TARP money. Hedge funds are not seeking bailouts, nor would they expect them if they started to go under. Hedge funds are not part of the state bureaucracy, nor do they have obligations to the state, nor to President Obama's preferred interest groups. They have obligations to their clients, and their clients probably want them to get as much of their money back from Chrysler as they can. It is unreasonable for Obama to demand private corporations to act in his own personal political interests. If hedge fund managers did this, and sacrificed their clients money in the process, it would be theft. And if they did it under threats of duress from the government then it would be political cronyism, and possibly criminal.

There's already been some of this strong-arming: the forced axing of GM CEO Rick Wagoner without prior approval of the shareholders; the unilateral ouster of the heads of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac; the coerced purchase of Merrill Lynch by Bank of America; the attempted punitive, retroactive, "personalized" taxes on AIG bonuses.

It is true that desperate times call for desperate measures. But in our haste to stabilize the financial system we should first guarantee that we leave our legal institutions intact. If we sacrifice one to save the other, we may soon find that we have retained neither. If we are willing to sell off long-standing rights of the debt-holder for temporary political gain, then the government will find itself unable to attract any new "partners" for future recovery efforts (such as the PPIP program).

We all want to help suffering autoworkers, but the Robin Hood model is unsustainable. Especially when the redistributor is King John.

Saturday, May 2, 2009

We Can't Stop Carbon Emissions

Labels: Climate Change, EnvironmentSo says Peter Huber:

We no longer control the demand for carbon, either. The 5 billion poor—the other 80 percent—are already the main problem, not us. Collectively, they emit 20 percent more greenhouse gas than we do. We burn a lot more carbon individually, but they have a lot more children. Their fecundity has eclipsed our gluttony, and the gap is now widening fast. China, not the United States, is now the planet’s largest emitter. Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa, and others are in hot pursuit. And these countries have all made it clear that they aren’t interested in spending what money they have on low-carb diets. ...

The grand theory for how the developed world can unilaterally save the planet seems to run like this. We buy time for the planet by rapidly slashing our own emissions. We do so by developing carbon-free alternatives even cheaper than carbon. The rest of the world will then quickly adopt these alternatives, leaving most of its trillion barrels of oil and trillion tons of coal safely buried, most of the rain forests standing, and most of the planet’s carbon-rich soil undisturbed. From end to end, however, this vision strains credulity.

His argument is simple: even if we (in the developed world) cut our carbon consumption markedly, the reduced demand will lower the price. Energy-starved developing economies will then take advantage of the lower price by ramping up their consumption by at least as much, and the net effect on emissions will be nil. We can't prevent them from doing this, nor we can afford to simply buy them off, because their sheer numbers are too great. In other words, we simply can't get past the economics of this even if we (in the developed world) were willing to sacrifice quite a lot to reduce emissions.

What can be done? Huber suggests that we cease spending time and money trying to hold back the inevitable tide. Instead we should invest in sequestering the carbon and sinking it back into the ground. This is best done, in Huber's mind, by investing in reforestation and other land use reform. In other words, Huber suggests taking better advantage of the earth's built-in stabilizers.

Would this be sufficient? Even Huber doesn't seem fully convinced. But there are reasons to think that the probability of sequestering working is greater than the probability of getting a bunch of treaties signed, ratified, and enforced. And sequestering comes with the added benefit of encouraging poor countries to grow out of poverty, rather than forcing them to stay poor.

For a different take, proposed by a Republican Congressman and member of the Pigou Club, see this letter.